The US-China trade war has escalated in recent days, with both countries announcing new tariffs on each other’s goods.

US President Donald Trump has said repeatedly that China will pay these taxes, even though his economic advisor, Larry Kudlow, on Sunday admitted that US firms pay the tariffs on any goods brought in from China.

So is Mr Trump wrong when he says the trade war is good for the US, and generating billions of dollars for the US Treasury?

And who will lose most as the conflict escalates?

Who really pays the US tariffs?

US importers, not Chinese firms, pay the tariffs in the form of taxes to the US government, confirms Christophe Bondy, a lawyer at Cooley LLP.

Mr Bondy, who was senior counsel to the Canadian government during the Canada-EU free trade agreement negotiations, says it is likely that these additional costs are then simply passed on to US consumers in the form of higher prices.

“They [the tariffs] have a strongly disruptive effect on supply chains,” he said.

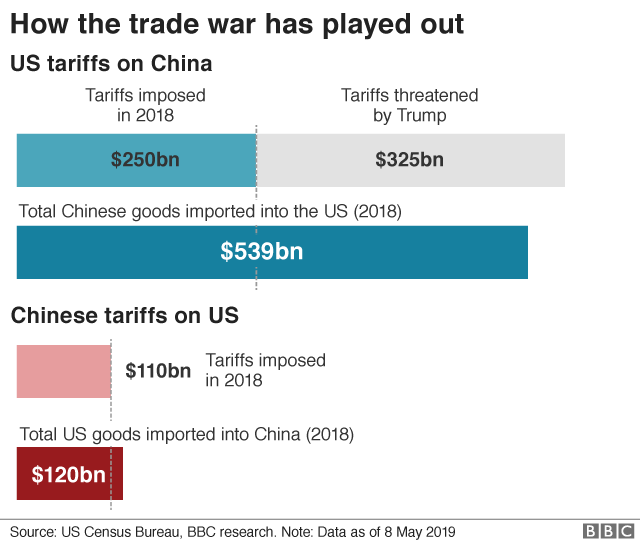

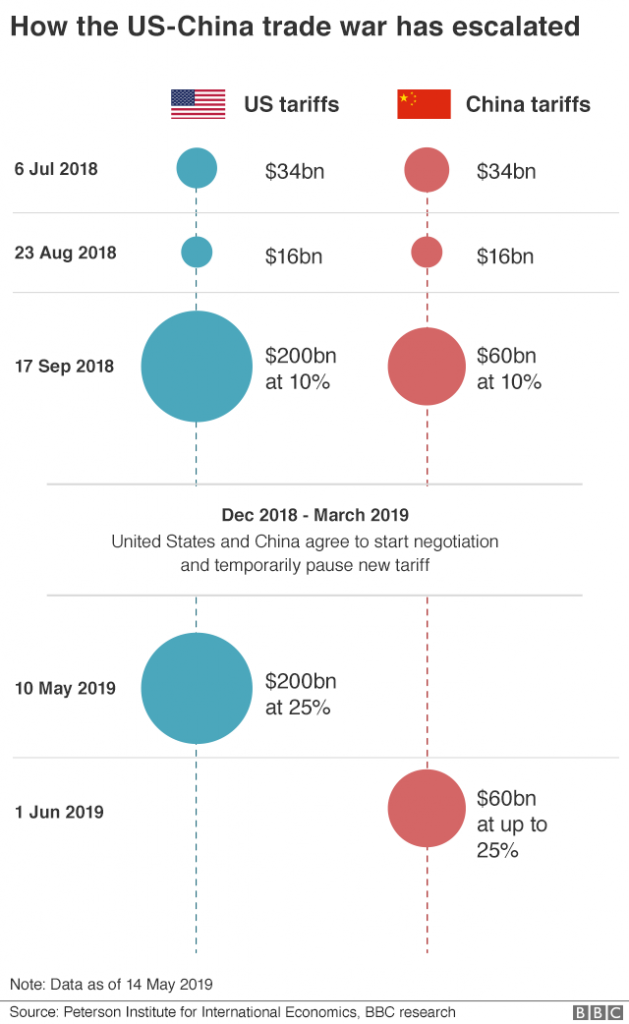

How the trade war has played out

What has the impact been on China?

China remains America’s top trading partner, with exports rising 7% last year. However, trade flows to the US slipped 9% in the first quarter of 2019, suggesting the trade war is starting to bite.

Despite this, Dr Meredith Crowley, a trade expert at the University of Cambridge, says there is no evidence that Chinese firms have cut their prices in a bid to keep US firms buying.

“Some exporters of highly substitutable goods have just dropped out of the market as US firms have started importing from elsewhere. Their margins are too thin and tariffs are clearly hurting them.

“I suspect those selling highly differentiated goods have not reduced their prices, possibly because US importers rely on them too much.”

What has the impact on the US been?

According to two academic studies published in March, American businesses and consumers paid almost the entire cost of US trade tariffs imposed on imports from China and elsewhere last year.

Economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Princeton University and Columbia University calculated that duties imposed on a wide range of imports, from steel to washing machines, cost US firms and consumers $3bn (£2.3bn) a month in additional tax costs.

It also identified a further $1.4bn in losses linked to depressed demand.

The second paper, penned by among others, Pinelopi Goldberg, the World Bank’s chief economist, also found that consumers and US companies were paying most of the costs of the tariffs.

According to its analysis, after taking into account the retaliation by other countries, the biggest victims of Trump’s trade wars were farmers and blue-collar workers in areas that supported Trump in the 2016 election.

Can’t US firms just buy their goods from other countries?

Mr Trump has said US firms that import from China should look elsewhere – perhaps to Vietnam – or better still buy their goods from American manufacturers.

But Mr Bondy says it is not so simple.

“It takes a long time for productivity and value chains to be reoriented and that all comes at a cost.

“Take the steel tariffs the US imposed last year – it is not like all of a sudden there are hundreds of new factories being built in the US.”

China is also a manufacturing powerhouse, dwarfing its nearest rivals, which makes it hard to replace it in global supply chains.

Have trade tariffs ever worked?

There is little evidence to suggest they have, say both Dr Crowley and Mr Bondy.

In 2009, President Obama placed a steep tariff of 35% on Chinese tyres, citing a surge in imports that was costing US jobs.

However, research from the Peterson Institute for International Economics in 2012 found the cost to American consumers from higher tyre prices was around $1.1bn in 2011.

Although about 1,200 manufacturing jobs were saved, it said, the additional money US consumers spent reduced their spending on other retail goods, “indirectly lowering employment in the retail industry”.

“Adding further to the loss column, China retaliated by imposing antidumping duties on US exports of chicken parts, costing that industry around $1bn in sales,” it said.

The one example usually given to defend tariffs is US President Ronald Reagan’s decision to impose steep duties on Japanese motorcycles in 1983.

The move is credited as saving struggling US bike-maker Harley Davidson from a surge of foreign competition.

But some have argued it was the company’s own efforts – including modernising its factories and building better engines – that really drove its turnaround.

Will the US tariffs force China to strike a deal?

Dr Crowley says the duties may draw China back to the negotiating table, but she does not expect them to offer radical compromises.

“Yes they are having more of a growth slowdown, and they export more to the US than vice versa, so they will suffer more from a trade war.

“But they are not really interested in changing their laws, and even if they did, do they really have the legal culture to enforce it?”

Mr Bondy thinks Mr Trump’s tariffs threats are more about whipping up his voter base and making headlines.

“Tariffs are easier to understand than the painstaking work of negotiating common sets of rules on things like the behaviour of state-owned entities, protection of intellectual property, fair access to markets and baseline protections for workers and the environment.”

Content is for general information purposes only. It is not investment advice or a solution to buy or sell securities. Opinions are the authors; not necessarily that of OANDA Business Information & Services, Inc. or any of its affiliates, subsidiaries, officers or directors. If you would like to reproduce or redistribute any of the content found on MarketPulse, an award winning forex, commodities and global indices analysis and news site service produced by OANDA Business Information & Services, Inc., please access the RSS feed or contact us at info@marketpulse.com. Visit https://www.marketpulse.com/ to find out more about the beat of the global markets. © 2023 OANDA Business Information & Services Inc.